Seneca entreated us to spare a little time each day to think of everything that could go wrong: “Reckon on everything, expect everything. Nothing ought to be unexpected by us.” Our minds should consider all scenarios: not just what is wont to happen, but what can happen.

Try as we might, we can’t seem to get comfortable with the consensus around the US election.

It’s hard to pinpoint precisely, but something does not feel right. We have come to rely on our intuition to avoid systematic errors in thinking. Oftentimes we start with some intuitive knowledge, which later can be validated or invalidated through rigorous research and analysis.

It was only in January that President Trump was hailed as the strongest incumbent ever to face reelection. Joe Biden’s depiction as a lackluster contender contrasted with Bernie Sanders’s surge in popularity. Betting markets gave the Vermont senator a 60 percent chance of winning the nomination.

A hasty unity among center-left Democrats who were disinclined toward a progressive political revolution propelled Biden from electoral failure to presidential nominee on Super Tuesday. Was the former vice president the most electable candidate the Democrats could rally behind? It was baffling. The party seemed to be in disarray.

A nearly universal lack of enthusiasm for Biden was twinned with skepticism about his ability to beat Trump. (Only Sanders could put up a good fight against the president, we believed, by mobilizing young voters.)

The coronavirus pandemic was a turning point. Trump’s fumbled response gave Biden the election advantage. People started believing that Biden could win. Races tightened even in traditionally red states like Texas, Montana, and South Carolina.

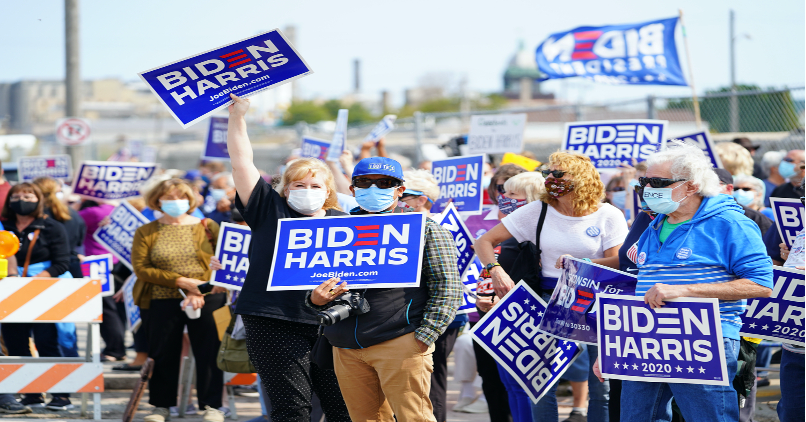

Once Kamala Harris joined the Democratic ticket as vice presidential nominee in August, the narrative became more powerful. A sizeable lead in the polls bolstered Democrats looking for an election sweep. Wall Street strategists put forth a bullish argument for stocks, putting aside Biden’s commitment to raising corporate taxes and increasing regulation.

The farcical first presidential debate laid bare Trump’s “psychotic unraveling,” as conservative writer Andrew Sullivan put it. He was crashing in the polls. In the face of his Covid diagnosis, some said that he may die before the election. People focused on the presidential line of succession. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi backed legislation to determine whether a president lacks the mental or physical capacity to carry out the job.

As we write, Biden’s nationwide lead over Trump has risen to 9.7 percent, according to an average of polls by RealClearPolitics. Democrats are ahead in all of the nine key battleground states. Among the likeliest scenarios from Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight polls is now a Biden electoral college victory of over 400. The blue wave is turning into a tsunami.

In just over six months, then, a storyline that started with I-can’t-believe-Biden-is-the-nominee shifted drastically; he won’t win; he can win; he will definitely win; wait, Democrats may actually sweep this thing! And guess what, it will be great for markets. On and on the story goes.

Has overconfidence set in?

Source: Shutterstock

If this year has taught us anything, it is to count on the unexpected. A pandemic, the shutdown of the global economy, the deepest recession and the highest unemployment since the 1930s, negative oil prices, the fastest bear market followed by new record highs for the US equity market—none of this was predicted.

Should we not at least consider how the consensus could be wrong on November 3? Ahead of the election consider this:

1. Polls conducted in the final 21 days before the last five presidential elections had a weighted-average error of 4 points. In 2016, the error was 4.9 points.

National polls can be accurate in identifying the preferred candidate and yet fail to identify the winner. The electoral college picks the winner of presidential elections, which means state polls are what really matter.

A systematic miss in election polls is more likely than people think. State-level outcomes are highly correlated with one another, so polling errors in one state are likely to repeat in other, similar states. State polls have experienced a weighted-average error of 5.3 points.

The educational divide is now one of the most important predictors of party support besides race. Failing to adjust for survey respondents’ education level was among the most important takeaways from the polling misses in 2016. While some pollsters have fixed this flaw by weighting education, not all have. Since highly educated voters are more likely to participate in surveys and to self-identify as Democrats, the potential exists for polls to overrepresent them.

“A Trump victory would be the biggest error in our modern era of mass polling,” Deutsche Bank strategist Jim Reid notes. “The largest error was in 1948 when President Truman won by 5 percent in spite of being behind by 4.4 percent in the final polls.”

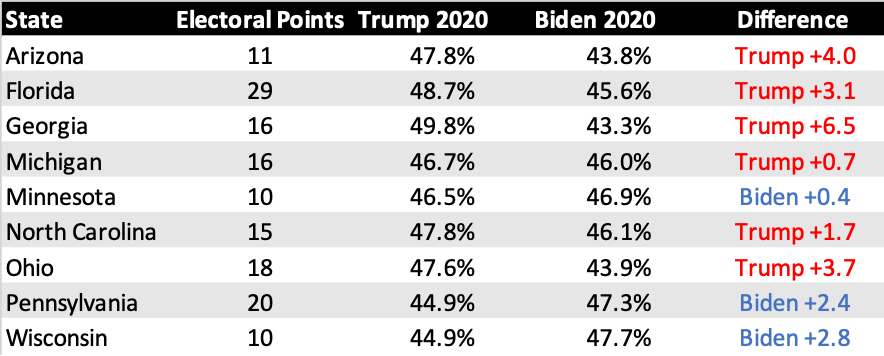

2. The most accurate pollster for state races in 2016 and 2018 was Trafalgar Group. This is what they are currently polling:

Source: Trafalgar Group

Trump’s path to a second term is clear: he can afford to lose 36 of the electoral votes he secured in the 2016 race and still win the election.

Thus he can lose Pennsylvania and Michigan and secure victory by carrying Wisconsin (or flipping Minnesota) and winning every other state he won four years ago. In 2016, Trump lost Minnesota by just forty-five thousand votes despite devoting limited money and attention there. His campaign is fixated on winning it this time.

Through an artful drawing of district boundaries, Republicans have locked in partisan advantages in key states. Even if Democrats turn out in larger numbers and win an even more decisive popular vote than they did in 2016, their chances of substantial legislative gains are limited by gerrymandering.

In Wisconsin, maps are crafted with such micro-precision that Republicans can win close to a supermajority of House seats even with a minority of the two-party vote. Wisconsin’s largest paper has called the election “the most undemocratic in the state’s history.”

3. There is little to no evidence for “shy Trump voters” who don’t tell pollsters their true intentions. In other words, there is no “silent majority.” About 11 percent of the electorate remains undecided, less than the 20 percent undecided from four years ago.

There is evidence that when the public is told that a candidate is extremely likely to win, as in the case with Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Biden in 2020, some people may be less likely to vote. Fact: a white male Democratic presidential nominee has not won over a majority of American voters since at least the 1970s.

4. When it comes to adding new voters to the rolls in key states, Republicans have swamped Democrats. In Arizona, Florida, North Carolina and Pennsylvania voter registration trends are more robust for the GOP than four years ago.

In Florida, Republicans added a net 195,652 registered voters from March to the end of August, while Democrats added 98,362 and other voters increased 69,848. In 2016, Trump prevailed in Florida by just 112,911 votes.

In Pennsylvania, Republicans added a net 135,619 voters from June to the final week of September, while Democrats added 57,985 and other voters increased 49,995. In 2016, Trump won the state by just 44,292 votes.

The Trump campaign wants to expand its core demographic base through registration and mobilization. In 2016, there were 2.4 million eligible white voters without college degrees who didn’t vote in Pennsylvania; 2.2 million in Florida, 1.6 million in Michigan, and 872,000 in Wisconsin, according to estimates compiled by the non-partisan Cook Political Report.

Trump’s door-to-door canvassing is paying off while Democrats ditched the ground game, citing virus concerns and explicitly backing vote-by-mail. Only just now has the Biden campaign restarted its in-person voter contacts in certain battleground states.

5. Trump supporters are more than twice as likely as Biden supporters to say they plan to vote in person on election day (50 percent versus 20 percent). By contrast, 51 percent of Biden supporters say they plan to vote by mail or absentee ballot (or have already voted this way).

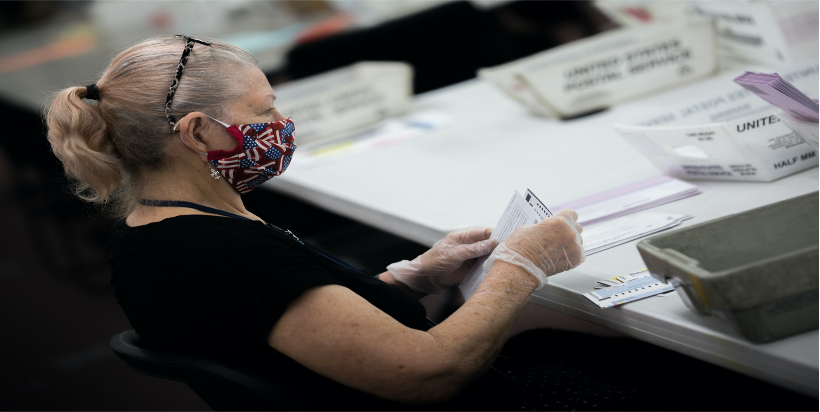

The conundrum is that millions of people voting by mail will result in more errors—and more rejected ballots. More than 550,000 mail-in and absentee ballots were disqualified in the 2020 primaries, a much higher number than four years ago.

Democrats’ big edge in early voting cannot be trusted as a result. Hundreds of thousands of votes are sure to be invalidated. For example, Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court recently ruled to throw out “naked ballots”—mail votes that aren’t sealed within two different envelopes.

States have a lot of power in deciding how the election will run. Today, Republicans control 30 state legislatures and Democrats only 19, with one state divided. These red-state legislatures enjoy 305 electoral votes, and 270 are needed to secure the presidency. There’s no question Republicans would benefit from the mass disqualification of mail-in ballots.

Source: Shutterstock

6. Historian Allan Lichtman, who predicted every presidential race since 1984, picked Biden in August to win the election. His 13 Keys model, articulated for the wider public in his 1996 book The Keys to the White House, favors Biden on 7 of the 13 prompts.

Lichtman notes that the Trump administration achieved no major success in foreign or military affairs, giving Biden the advantage. That’s one key.

However, we would rank the Abraham Accords, signing of a peace treaty between Israel and the United Arab Emirates signed on September 15, as a major milestone. This would flip Lichtman’s model in favor of Trump.

7. No incumbent has ever won reelection during a recession. What’s different this time is that although the economy is experiencing its worst downturn since the 1930s, the stock market is at record highs. That’s never happened before.

Socionomic voting theory holds that social mood as reflected by the stock market is a more powerful indicator of reelection outcomes than economic variables such as GDP, inflation and unemployment. By studying all US presidential elections since 1824, the Socionomics Institute found that while GDP is a significant predictor of the incumbent’s popular vote margin in a simple regression, it’s inconsequential when combined with the stock market in a multiple regression.

According to a study by LPL Financial, when the S&P 500 has been higher in the three months before the election, the incumbent party has a strong chance of winning. This has been true 87 percent of the time since 1928 and 100 percent of the time since 1984.

Based on this reasoning, four more years of Trump is a real possibility if the S&P 500 is trading above 3,294 on election day (the closing level on August 3). We are sitting 7 percent higher than that.

8. We are in the strongman era. In 2016, President Trump joined the world’s swelling ranks of authoritarian leaders promising to lead national revivals—Putin in Russia, Xi in China, Modi in India, Erdogan in Turkey, Duterte in the Philippines, Orban in Hungary, and Salman in Saudi Arabia.

Trump’s blend of nativism, bigotry, grandiosity, and coarse speech, combined with a colossal ego, swaggering political style, and scant respect for institutions are all hallmarks of a strongman. With public trust in government near historic lows, we argued Trump could get away with more controversy than any past president. This led to our oft-cited phrase: “Don’t fight The Donald.”

If Trump loses in November, it would be an oddity in international politics—a break from the pattern of strongman resurgence. Each of Trump’s peers have gotten stronger in recent years.

Source: Shutterstock

So, putting it all together, here’s where we stand.

A Biden victory will prompt little surprise. Democrats will sweep if the polls are accurate. There won’t be a contested election. Despite Trump’s threats to challenge the result, he will have no choice but to concede. The military and courts won’t have to get involved. The GOP won’t put up a political fight. As in the case of every fallen authoritarian, the people closest to Trump will distance themselves from him.

This would be a good outcome for stocks. The dollar may fall and bond yields may rise on expectations of more government spending.

Even if the GOP keeps the Senate, they will not obstruct legislation. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell will have every incentive to compromise given how exposed Republicans look going into the 2022 Senate elections. Democrats will defend 12 seats while the Republicans will defend 22 seats.

But what if President Trump occupies the White House for another four years?

If Trump wins the electoral college without winning the popular vote, especially after Biden having been the clear favorite all summer, it will be hard for most Americans to trust the integrity of the election.

As it is, Democrats and others on the Left have never really come to terms with the results of the previous election. This time, it would be worse. How can they fail to beat a candidate as unpopular as Trump during a pandemic and a devastating recession?

They won’t find solace in their thinking that 2016 was a “mistake”; that their fellow Americans had been manipulated or simply hadn’t understood what was best for them. They won’t be able to blame Facebook or Russia. They will convince themselves that Republicans are, in one way or another, cheating. Mass disillusion with electoral politics as a means of change will result in more social upheaval and political violence across American cities.

Notwithstanding such unrest, stocks should do well in this scenario, even if there is a brief blip, as the status quo remains unchanged. The dollar and government bonds may rally along with the world’s anxiety about Trump’s second term. Renewable energy stocks may implode.

That’s what investors should prepare for. Nothing ought to be unexpected by us.

Source: Shutterstock