China’s economy is reopening, the US and Europe have avoided a much-feared recession, and the International Energy Agency (IEA) has raised its forecast for global oil demand growth to a record of almost 102 million barrels per day for 2023.

US shale oil output growth is still modest, meanwhile, and OPEC supply dipped last month. OECD oil stocks remain low by historical standards, and Western nations have just tightened sanctions against Russia, the world’s largest petroleum exporter.

It seems like a recipe for a very tight oil market. And yet the Brent oil price is flat year-to-date and 15 percent lower than its level on the eve of Russia’s invasion. What’s going on?

Here’s a suggestion: what if oil is starting to price in a negative demand shock from the global energy transition?

We believe that the booming market for electric vehicles, or EVs, will reduce oil demand substantially and weigh on prices much sooner than most expect. The structural shift in global energy markets has already begun.

Professor Rudi Dornbusch once said, “In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.” If ever there was a situation that exemplified his words, it is now with the global adoption of electric vehicles.

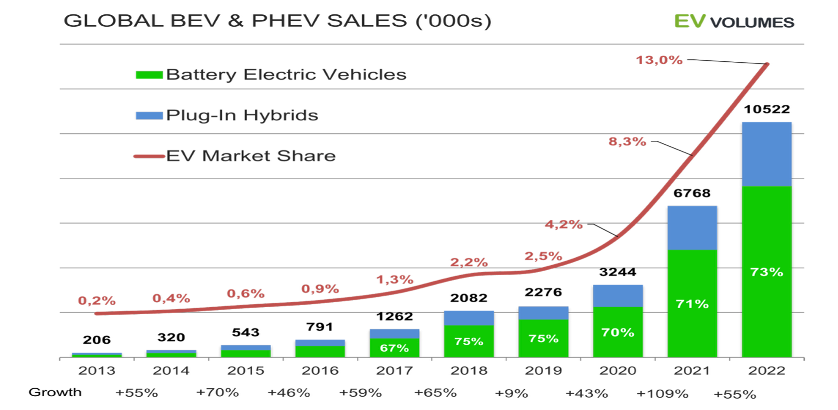

Around the world, only 120,000 electric cars were sold in 2012. In 2022, sales averaged close to 200,000 per week. Ten million new EVs were delivered last year, an increase of 55 percent from 2021. EVs made up 13.0 percent of all light vehicle sales, compared to 2.2 percent in 2018 and 8.3 percent in 2021.

In 2020, the IEA projected that the global share of EV sales would not top 10 percent before 2030. We’ve exceeded that threshold eight years early. Researchers now expect that EV market share will approach 40 percent by the end of the decade.

Source: Bloomberg NEF

China, the world’s largest auto market, is leading the way in the shift to green transportation. Sales of electric vehicles are soaring. Only 5.6 percent of new cars sold in China in 2020 were electric, a level that hit 13 percent in 2021. With sales of around six million EVs last year—more than the rest of the world combined—it was 25 percent.

China’s goal of having 40 percent of domestically sold vehicles be EVs by 2030 is likely to be met much sooner. At the end of 2022, EVs made up just 5 percent of the total passenger fleet in China, a figure that’s expected to rise to 32 percent by 2030.

To achieve this breakneck adoption, China is building charging infrastructure at lightning speed.

In 2022, China nearly doubled its installed EV charging piles, hitting 5.2 million units. It built 650,000 public EV chargers—ten times the number in the US. In Guangdong province alone there are now 383,000; America has less than half that.

“Developing new energy vehicles is essential,” proclaimed China’s President Xi Jinping as he wandered through a Shanghai electric vehicle factory in 2014. “It’s essential for China’s transformation from a big automobile country to a powerful automobile country.”

With EVs, China saw an opportunity to leapfrog automakers in the US, Germany, and Japan. China accounts for 95 percent of new registrations of electric two- and three-wheeler vehicles and 90 percent of new electric bus and truck registrations worldwide.

Eighty percent of all EV batteries come from the mainland, with China’s CATL and BYD supplying half of the total, even to competitors like Tesla and Toyota. China processes the majority of the world’s critical minerals, including lithium, graphite, and cobalt, and it produces two-thirds of the cathodes and anodes used in batteries.

With lithium prices falling and domestic battery inventories having tripled in 2022, the good news is that prices will come down for EV-makers and batteries won’t be a near-term bottleneck for growth.

Source: Xinhua

Chinese-made EVs will soon overrun urban areas worldwide. Auto exports have tripled in two years and China is now the world’s second-largest vehicle exporter, behind long-time leader Japan. If not for the pandemic-related supply chain bottlenecks and acute cargo-space shortages, the export boom would have been even bigger.

BYD started out as a mobile phone battery maker before manufacturing other electronics, auto components, and finally electric vehicles. It has ordered its own auto transport ships and may become a full-fledged shipping services provider. BYD’s discussions around buying Ford’s German manufacturing facility is another sign of things to come.

According to Charlie Munger, vice chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, BYD is so much ahead of Tesla in China that “it’s almost ridiculous.” And now Chinese EV companies, which are fiercely competitive, are prepared to fight for a piece of the global auto market. The result will be lower prices for consumers everywhere and even faster EV adoption than most foresee.

New regulatory targets in the European Union and the US now aim for an EV share of at least 50 percent by 2030, and several countries have brought forward bans on internal combustion engines in vehicles to 2030 or 2035.

In India, the nation with the fastest-growing oil consumption, 30 percent of auto sales and 80 percent of two-wheeler sales may be electric by the end of the decade. These are relatively unambitious figures. In 2022, India’s EV sales tripled and surpassed 1 million for the first time, accounting for 4.7 per cent of overall automobile sales. Two-wheelers made up 63 percent of the total.

Source: SCMP

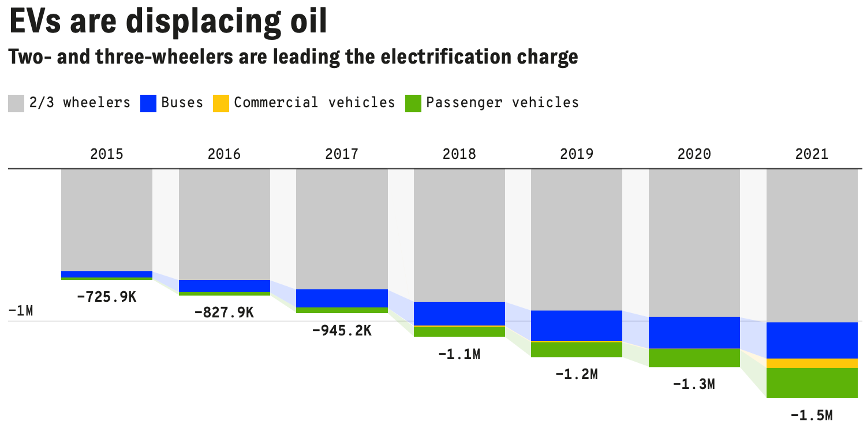

There are now almost 30 million electric vehicles on the road, up from just 10 million at the end of 2020. Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) analysis shows that this has reduced daily oil demand by about 1.7 million barrels. And the EV boom is just getting started.

There are ten times as many electric scooters, mopeds, and motorcycles on the road than electric cars, which already account for nearly half of all sales of those vehicles and two-thirds of the reduction in oil demand.

Passenger EVs underpin only 15 percent of oil-demand displacement. However, EV deployment in line with the pledges and announcements suggests oil displacement (excluding two- and three-wheelers) could be 4.6 million barrels per day by 2030.

For context, this is roughly equal to the combined oil consumption of France, Germany, and the UK. It would reduce the anticipated global growth in oil demand by 70 percent.

Oil demand from passenger cars, two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and buses has already peaked. The only segment contributing to growth is commercial vehicles. Conversely, the EV share of light commercial vehicles in China has increased from less than 1 percent to 10 percent over the past two years, with no signs of slowing down.

So, according to BNEF, the peak in gasoline demand will occur in 2026, followed by the peak in demand for all types of oil for use in transportation in 2027.

Source: Bloomberg New Energy Finance

This leads us to the following conclusions:

(1) According to various forecasts from BP, the IEA, and OPEC, global oil demand will rise 5 to 8 million barrels per day by 2030. Our contrarian view is that faster-than-expected EV adoption will flatten out the world’s oil demand by the mid-2020s. At around 100 million barrels per day, it is the same today as it was five years ago.

(2) Oil briefly surged to $139 a barrel shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We won’t return to those nosebleed levels for a long time to come. Oil displacement from the global EV fleet will have a significant impact on world oil prices.

(3) As doubts about the strength of long-term oil demand grow, OPEC+ will increase output to maximize revenues. Even in a well-supplied market, countries will prioritize raising production volumes rather than trying to manage a price level.

(4) China will launch a charm offensive to keep its hold on important auto export markets without igniting political backlash. China-made EVs increased their market share in Europe from 2 percent in 2020 to 11 precent in 2022. We’re moving into an era where economics will trump politics.

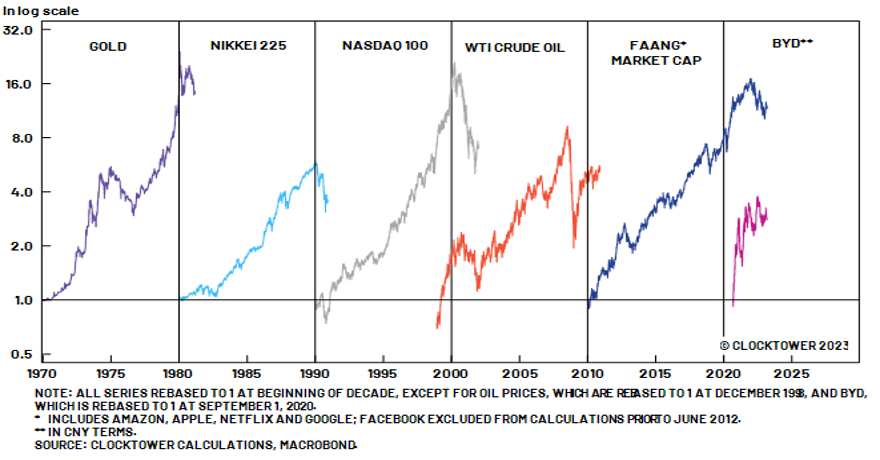

(5) We have been searching for an asset that would best capture the investment zeitgeist of this decade: the race to zero emissions. BYD is in the running.

Source: Clocktower Group